- Home

- William Kowalski

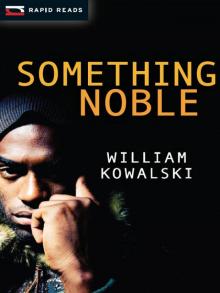

Something Noble

Something Noble Read online

SOMETHING

NOBLE

WILLIAM KOWALSKI

Copyright © 2012 William Kowalski

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Kowalski, William, 1970-

Something noble [electronic resource] / William Kowalski.

(Rapid reads)

Electronic monograph.

Issued also in print format.

ISBN 978-1-4598-0014-4 (PDF).--ISBN 978-1-4598-0015-1 (EPUB)

I. Title. II. Series: Rapid reads (Online)

PS8571.O985S65 2012 C813’.54 C2011-907749-3

First published in the United States, 2012

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011943697

Summary: In order to save her son’s life, a single mom must try to convince a selfish drug dealer to donate one of his kidneys to his half brother. (RL 3.0)

Orca Book Publishers is dedicated to preserving the environment and has printed this book on paper certified by the Forest Stewardship Council®.

Orca Book Publishers gratefully acknowledges the support for its publishing programs provided by the following agencies: the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Design by Teresa Bubela

Cover photography by Getty Images

ORCA BOOK PUBLISHERS

PO Box 5626, Stn. B

Victoria, BC Canada

V8R 6S4 ORCA BOOK PUBLISHERS

PO Box 468

Custer, WA USA

98240-0468

www.orcabook.com

Printed and bound in Canada.

15 14 13 12 • 4 3 2 1

To all those who need a second chance

CONTENTS

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Acknowledgments

CHAPTER ONE

I just want to tell you straight up that this story has no happy ending.

But it doesn’t have a sad ending either. It’s a story about being a mom, so it has a lot of happy and sad in it. Like motherhood itself, it has no ending at all.

That’s because you never stop being a mom. You don’t stop when your kids go to sleep at night. You don’t stop when they grow up and move away. Being a mom is not just a job. It’s an identity. Maybe you already know what I’m talking about. If not, you will by the time you’re done hearing my story.

My life has never been boring. I’m not an important or exciting person, but sometimes some pretty wild things happen to me. Usually they don’t come right on top of each other like this though.

This is the story of one remarkable year that was full of one wild thing after another. It was a year that changed my life and the lives of everyone I cared about. And it starts in my least favorite place of all: a doctor’s office.

Let me take you back to that doctor’s office right now.

* * *

My son, Dre, is sixteen years old. He’s been feeling sick for a while. We’ve been having a lot of tests done. Now we’re sitting and waiting for the doctor to come talk to us.

Dre feels too sick to be nervous, so I’m nervous for both of us. He lies on the exam table with his arm over his eyes. He’s so tall that his feet hang way down off the end of the table. I still can’t believe how big my baby is. I carried him on my hip for so long sometimes I can still feel him there. Now look at him. He’s a giant with dreadlocks. So handsome the girls can’t take their eyes off him.

I was only sixteen myself when I had Dre. I try to imagine him becoming a father at this age. It’s a horrible thought. I didn’t know a damn thing when I was sixteen. For the millionth time, I think about how amazing it is that we even survived. I was so stupid when I was that age. So young and stupid.

But here we are. We made it through a lot of bad times. Only now my baby is sick, and I have this horrible feeling that more bad times are around the corner.

When I get nervous, I talk. So I keep on chattering away to Dre, even though he isn’t answering me.

After a while he says, “Mama, give it a rest. I’m too sick for small talk.”

So we sit and wait in silence.

Finally the door opens. A new doctor walks in. He stops and looks at Dre, then at me. Then he looks at his chart, like he’s making sure he has the right people. We get that a lot. That’s what it’s like when your kid’s skin is a different color from yours. I guess people wonder if you’re just borrowing him or something.

“Señora Gonzalez,” says the doctor. “Buenos días. Me llamo Doctor Wendell.”

I get that a lot too. People think I don’t speak English just because I look Latina. I don’t even get mad anymore. I don’t have the energy.

“Hi,” I say. “How you doing, Doctor Wendell.”

“Fine,” says the doctor, without missing a beat. And I realize he wasn’t being rude. We live in a big city. He must meet a lot of people who don’t speak English. So maybe he’s not so bad after all. He closes the door.

“Let’s talk about Dre,” he says. He pronounces it Dree.

“It’s pronounced Dray,” I say.

“Sorry,” says the doctor. “I know you weren’t expecting to meet a new doctor today. So let me tell you about myself. I’m a kidney specialist. I was called in because of the results of Dre’s tests. I think the reason Dre feels so sick all the time is because he might have kidney problems.”

I nod. I knew it was going to be something serious.

“What kind of problems?” I ask.

“Well, the job of your kidneys is to clean the impurities out of your blood. If they can’t do that, your blood gets dirtier and dirtier. It’s like you’re being poisoned. So what’s going on here is that Dre’s kidneys need some help doing their job.”

Dr. Wendell puts down the clipboard and waits for me to talk. It used to be that doctors never had time for us. We were just one more poor family of color. I used to hate it. It made me feel like our lives were unimportant to them. But now they are spending more and more time with us. They look at us in a new way now. And even though it sounds crazy, I hate this even more. It shows how serious Dre’s case is. I almost miss the days when we weren’t worth paying attention to. At least then nothing was really wrong.

I look at Dre. He hasn’t moved. I grab his toe and wiggle his foot.

“Well, baby,” I say, “at least now we know what the problem is.”

“Mmm,” says Dre. That’s the sound he always makes when he’s sick. I can tell he feels horrible.

“Is it one kidney or both?” I ask.

“I’ll need to run some more tests to be sure,” says Dr. Wendell. “The nurse will take your blood, Dre.”

“Mmm,” says Dre again. He’s so sick he doesn’t even complain about one more needle. The nurse comes in again and draws another vial of blood. Dr. Wendell promises to call us as soon as he gets the results. Then I help Dre out to the car, and we head home.

“What time is it?” he asks.

“Three o’clock,” I say. “Why

?”

“Because I gotta go do my paper routes.”

“Uh-uh,” I say. “No way. You’re gonna have to give those up. The doctor said you gotta rest.”

“But, Mama,” says Dre. “What about the money?”

Dre makes about three hundred bucks a month from his two paper routes. It might not sound like much, but it makes a big difference to us. Yet our neighborhood is getting worse and worse. I won’t be sorry to see him stop walking the streets by himself.

I got mugged last year right in front of my own house. Broad daylight. He pointed a knife at me and everything. I didn’t get hurt, but I was scared to death. And he took the twenty bucks I had on me. That was twenty bucks I could not afford to lose.

I would move to a safer neighborhood, but moving costs money. Right now I’m just keeping it together financially. I’m mostly unemployed. I only have one job, as opposed to my usual three or four. We have enough to eat and pay the rent. But I’m just one flat tire or one speeding ticket away from being bankrupt. And the house is mine. I’m not giving it up just because punks have taken over the east side of the city. They’ll have to kill me first.

“Forget about the money,” I say. “We’ll figure something out.”

“But what?” Dre says.

“I dunno,” I say. “You’re too young to worry about these things.”

“No, I’m not,” he says. “You were my age when you had me.”

“Let me worry about money. That’s my job. You just take care of yourself. That’s all that matters.”

“I’m not all that matters. There’s Marco too,” says Dre quietly.

I love him for saying that. I look out the window so he doesn’t see me crying.

CHAPTER TWO

Our house is a tiny bungalow. It’s on a side street just off one of the busiest avenues in the city. The front yard is a postage stamp. The porch roof is about as big as a child’s umbrella, and about as good at keeping you dry when you’re fumbling for your keys in the rain. Inside, there is just a living room, a kitchen, two bedrooms and a bathroom. Each room is about the size of a phone booth. But it’s mine, dammit. I bought it with my own money, back when things were better. And you better believe I keep it clean. My boys both knew how to make their own beds by the time they were five years old. And if you use a plate or a fork, you wash it. Just because we’re poor doesn’t mean we have to live in filth. You can be poor and clean at the same time.

Marco, my other son, is six years old. He’s taking a nap on the couch. His digital camera is on a cord around his neck. Marco loves to take pictures of anything and everything. My dream for him is that someday he’ll work for National Geographic.

Ernest, his dad, is waiting for me. Ernest’s parents are both from China, which means Marco is half Chinese, a quarter Latino, and a quarter white. The white comes from my dad, the Latino from my mom. Dre’s father was black, so Dre is African, European and Latino. When we’re all together, the house looks like the lobby of the United Nations.

“You let him sleep with this thing on?” I say. “He’ll strangle to death.” I take the camera off Marco’s neck.

“That’s an old wives’ tale,” says Ernest. “If he started choking, he’d wake up. Besides, I tried to take it off him and he wouldn’t let me.”

“Sometimes those old wives were right,” I say.

Ernest is wearing the kind of clothes I hate on him: a tight muscle shirt and jeans that show off how much he’s been going to the gym. He never worked out once during the years we were married. Sometimes I wonder if he’s trying to get me back, making me jealous by showing off his new body. It ain’t working.

I keep him waiting while I go with Dre to his room and help him take off his shoes. I make him lie down to rest. Then I go back out into the living room.

“What’s going on?” Ernest asks me. He crosses his arms and waits. Ernest is mostly bald, and when he’s concerned, he doesn’t just wrinkle his forehead. He wrinkles his whole scalp.

I fill him in. He nods.

“Well, you just let me know if there’s anything I can do, baby,” he says. “Anything at all, I’m there for you.”

I hate it when he calls me baby. That’s another thing he never did when we were married. I would like nothing better than for him to just go away and leave me alone. But we have a son together, and I need his support.

And at least Ernest isn’t in jail, which is more than I can say for some people’s fathers. Ernest has a decent job, and he believes in taking care of his kid.

“I’ll need you to help with Marco,” I say. “And I hate leaving Dre alone while he’s this sick. I know he’s not your kid, but if you’re here with Marco anyway, it doesn’t matter, right?”

Ernest nods.

“No problem,” he says. “Dre is a great kid. We always got along well.”

“I have to go to work now,” I say. “Can you stay with them until I get back?”

“Sure thing, baby,” says Ernest. He starts moving in closer, for what reason I am afraid to ask, so I dodge him and go into the bathroom. It’s going to take a lot more than this to make up for what he did. But I don’t even want to think about that right now. I need to start getting ready for work.

I’m trained as a continuing care assistant. I go into people’s homes and do some nursing and some light housekeeping as they recover from illnesses. Or sometimes I just sit with them while they die. I feel like it’s important work. So do my clients. The only ones who don’t seem to feel that way are the ones who sign my paycheck. When the work is steady, it’s not a bad living. It’s enough to pay the bills. But it hasn’t been steady for a long time. This economy is destroying us.

I could drive to work. But I decide to leave my car at home to save gas money. I take the bus a few miles down the road to a senior citizen’s apartment complex. This is where I’m working right now. I let myself into the apartment and call out:

“Miss Emily! It’s Linda Gonzalez.”

I don’t hear anything, but I wasn’t expecting to. I go into the bedroom. Miss Emily is asleep. She’s a very old, very tiny woman who is dying of cancer. She doesn’t have long left. I stroke her hand lightly. She gives a little moan.

“It’s Linda, Miss Emily,” I say again. “You need anything?”

Miss Emily is well cared for. She’s one of the lucky ones. A lot of poor people die alone, in what you might call undignified circumstances. That means lying in their own filth in the middle of a public hospital ward. Not Miss Emily. I guess she saved enough money in her working life so she could afford to die in private. Kind of depressing when you look at it that way. Isn’t there more to life than that? Working until you get old and die? Sometimes my life feels like that’s all it is. It’s my kids that make it all worthwhile.

Miss Emily wakes up enough to press her morphine drip. The pain must be pretty bad. I read her chart. The visiting nurse hasn’t left much in the way of orders. She knows the end is near. Right now we’re just keeping her comfortable. I pull back the sheets from her feet and look at her toes. They’re starting to curl. That’s always a sign that the end is coming. You won’t find that in any textbook. It’s just a trick I picked up from nurses who have been on the job a long time. We know a lot of things they don’t teach you in medical school.

There’s not much for me to do. The place is pretty clean. There are no dishes in the sink, no meals to be made. So I sit down next to Miss Emily’s bed and pick up the book that’s sitting on the floor. The title is The Audacity of Hope by Barack Obama.

“Let’s see,” I say. “Where did we leave off ?”

I read about when Mr. Obama’s mother was dying. It’s funny to think that the president of the United States of America is just as powerless against cancer as the rest of us.

It doesn’t matter what the words are. Miss Emily probably doesn’t understand me anyway. But I know she can hear the sound of my voice, and she finds it comforting.

Suddenly I feel my cell phone go o

ff. I have it set to vibrate. I stop reading and go into the other room.

“Hello?”

“It’s Ernest. You gotta go to the hospital.”

CHAPTER THREE

I’ve got that feeling every mother dreads. Which one of my boys is it? Please, God, nothing serious, okay? I can’t deal with another thing right now. I’m too tired.

“Why? What happened?”

“It’s Dre. He collapsed. I called nine-one-one. They took him away in an ambulance.”

“Okay,” I say, as calmly as possible. “Can you stay with Marco?”

“I’ll take him home with me,” says Ernest. “He can spend the night at my place.”

I hang up on Ernest and call my head office. I explain the situation to them, hoping they will let me leave early. They say it all depends on if I can get someone to replace me. Which really means it’s my problem, not theirs.

I call the girl who was supposed to come on next and ask if she can come in a few hours early. She says she wasn’t planning on it. So I’m reduced to begging her. My son is in the hospital, I say. Please. Just this once. I’ll make it up to you somehow.

She agrees, but I will owe her. I don’t care. I would mortgage my soul to help my kid. I wait until she shows up. Then I leave for the hospital, riding the slowest bus on the planet. After what feels like ten lifetimes, I finally make it to my son’s bedside. He’s in a little room in the ER.

I promised myself a long time ago I wouldn’t shed any more tears in front of my children. But when I see his face, looking scared and exhausted, it’s all I can do to keep it together.

“Hey, bunny boy,” I say. That was my nickname for him when he was a baby. Normally he would yell at me for using it. How I wish he was healthy enough to be embarrassed.

“Mama,” he says.

“Listen, you hang in there,” I say. “We’re gonna get you fixed up.”

Dre doesn’t answer. But I gotta keep talking. This is one of those times when silence is not golden.

The Good Neighbor

The Good Neighbor Eddie's Bastard

Eddie's Bastard Jumped In

Jumped In Something Noble

Something Noble The Adventures of Flash Jackson

The Adventures of Flash Jackson Just Gone

Just Gone The Way It Works

The Way It Works Epic Game

Epic Game